CHAPTER 8 – PROTECT AND SURVIVE

Catching The Smallest Bass

Over twenty years ago a major change occurred in my bass activities. Conventional fishing for bass of respectable size was first reduced, and then abandoned altogether, never to be revived. It is strange now to reflect on this conscious renouncing of the habits of more than forty years. There would be no more three to seven-pounders, and no more occasional eight or nine-pounders. Instead, the emphasis would now switch to young bass in their nurseries, right down to the tiny post-larvae that came into nursery estuaries early each summer.

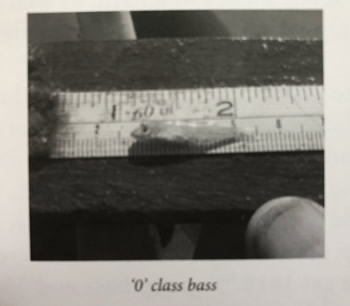

What made me take such a strange step? It is difficult to pinpoint a single cause. Many subtle influences were at work, all pointing me in the same direction – to investigate the early stages of bass, about which little was known. Scientists at the Lowestoft laboratory and regional fishery offices were asking questions to which I had no answer, and about which the Marine Laboratory at Plymouth had only limited information. It was Judith who finally made up my mind, when she invited me to comment on the draft of her degree thesis. I had been sending her samples of young fish for her study on the gill parasites of bass. It was an excellent draft, and I had little to comment on until I came to the section on spawning, and that pulled me up short. ‘Spawning’ she wrote ‘ …. occurred only in the waters off southwest England, and the tiny ‘0’ group bass were found only in southwestern estuaries’. That, indeed, was the received wisdom of the day, but I had, for years past, been finding spawning bass in springtime, in the river mouths of west Wales including Anglesey. I felt sure that the ‘0’ groups would be present in the same estuaries; in the marsh creeks further up.

The situation called for a major project to check my theories. Eight west – coast estuaries were selected, ranging from Hayle in Cornwall, to Dwyryd in north Wales. They would be sampled at fortnightly intervals from May to October, over a two-year period. I had some NERC grant money left over from the tagging exercises, and I knew that this would meet much of the cost of travelling and subsistence. NERC agreed to this, but first they wanted evidence that the project had a reasonable chance of success. A pilot study was called for. I selected two of the eight sites, my local Camel estuary in north Cornwall and the Dyfi in mid-west Wales. For four months, from April to the middle of August, the Camel was netted regularly, and not a single bass was found. Then on 17th August, Bob Cox, who had joined me, spotted two tiny fish in the net. Though entirely without pigment and scales, we thought they might be bass. I took them home and got out my textbooks; they were, indeed, bass. The next time out was with Nigel Hester, who had been involved in the earlier netting, we found fifteen. Then a quick trip to the Dyfi showed that there too, ‘0’ group bass were present. lmportantly, it was found that they loved the spartina, and were getting right in amongst the grass. Modest results indeed, with fewer than 30 fish for the two nettings combined, but it was enough to satisfy NERC, so the project went ahead. Later it became apparent that we had been sampling a very poor year class (1981), and we had been lucky to get even that number of bass. In the two following years the project proper, delivered to the tune of over 25,000 ‘0’ group bass from the eight estuaries, plus 1,000 one-year-olds. The runnels intersecting the spartina marshes, especially on the Dyfi, Mawddach, and Dwyryd were, as portended on the Dyfi, very productive.

The Camel was one of our eight sites, and it continued to produce meaningful results year after year. It remains the ‘banker’ for assessing relative year class strengths on the northern side of the southwest peninsula. The best site, one of many in the Camel that can produce on their day, is Trewornan Dam, which is unchanging and produces consistently acceptable results.

Sixty miles up the coast from the Camel is the Taw estuary. It too has been regularly netted, giving excellent results. Unfortunately these results cannot be used for abundance assessments because the sites are constantly changing. The Taw produced the biggest ever catch of 17,000 fish, when an exceptionally attractive site formed on the edge of the main channel. However, on our next visit, a month later, the site had vanished. Nevertheless, the Taw provided valuable data about the winter survival of the ‘0’ groups. A deep narrow branch channel at Braunton was found to attract ‘0’ groups throughout the winter. Netting before and after severe cold spells told us much about their capacity for survival. There have been very few significant cold spells in the last twenty years, so losses have been small. An exception was the five-week cold spell in January and February 1986 during which an estimated 58 per cent was lost. Adding this information to other results, it was possible to conclude that it was the length of the cold spell rather than its intensity that mattered. Casualties began to occur when the spell was over three weeks in duration. The smallest fish died first, with any that were under 60mm fork length at the onset of the cold spell being likely to die, together with most of those between 60 and 70mm.

The Taw in winter was also the scene of a trial dye marking of young bass. If a success, it was intended to do an estimate of the total ‘0’ group population of the Taw estuary. The trial was a success; the ‘0’ groups ‘took’ the dye well, and in the subsequent recapture, up to six months after marking, the dye was still clearly visible. However, the planned count was never done because to cover such a large estuary, adequately, would have cost too much. Someday it may be tried, perhaps in a smaller estuary such as the Camel.

In 1984, two years after the Camel monitoring began, I was asked to try a similar monitoring on the Tamar, where a student of Dr. Peter Reay, lecturer at Plymouth Polytechnic, was studying young bass. Eric, a long time partner in all my bass activities, knew of a likely spot at Landulph, where there was a big spartina marsh intersected by numerous shallow creeks. We tried them all and decided that the first two (counting from the church) looked the most promising. They delivered well right from the start, and became the ‘banker’ for estuary sites on the southern side of the southwest peninsula. Trials in the Yealm, Fowey, and Fal gave similar year-class proportions to those of the Tamar. Meanwhile Derek Goodwin, who had been a regular participant on the Camel and Fowey, switched his attentions to the Helford, and together with John Bridger he persevered for seven years in what was proving to be a difficult estuary (because there were no significant spartina marshes to concentrate the bass). Although numbers were modest, they bore the same year-class relativities as the Tamar. Derek has now switched to the Fal, where John and I had experienced poor results in an earlier study. The loss of John, in a boating accident, was a tragic setback, but other willing helpers have been found, and already two promising sites, not previously discovered, are raising prospects.

Over the years since those early trials many other estuaries have been identified as bass nurseries. It is now safe to say that all estuaries south of an imaginary line running from the Wash to the Solway Firth are, if not polluted, nurseries for young bass. The warm water from coastal power stations also attracts them.

Netting techniques and equipment have been fully described in earlier published papers, but the following notes will give a good idea of what ‘0’ group sampling actually entails.

It is 5th August on a warm sunny day. There is a light westerly breeze, perfect conditions for netting the Tamar ‘0’ groups. The team of four has assembled and are pulling on their thigh boots or chest waders. Besides Eric and me, as usual, there is Dr. Edward Fahy of the Irish Marine Institute. He has come over to get some ideas from us, because his Irish sampling has not, so far, been very good. Also there is Malcolm Gilbert, who, having met Edward in Ireland, has arranged this visit. We head off along the marshes towing the net in its large fish box. After barely a mile we cross a low dyke on our left and find ourselves at the start of a big spartina marsh. There is a small creek in front of us not yet reached by the rising tide. We move on round the edge of the spartina and come to a second creek, ‘T’ shaped at the head like the first. There is two or three feet of water, slightly cloudy, and rippled by the westerly breeze. As we have found that the ’0’ groups tend to go with the wind, we decide to net the east arm. Malcolm takes one end of the net and draws it across to the far bank. He then starts pulling up the creek. Meanwhile I have picked up the other end of the net and also begin pulling, keeping abreast of Malcolm. The deepest water is on his side and he is at pains to keep close to the far bank. It is shallower on my side and at the start the net does not reach the nearside bank, but only mullet see it as an escape route. No bass escape, and soon the creek narrows and the net is drawn up to the tiny beach at the head. We leave the centre in the water, and then gradually ease it up, whilst we count the catch, returning them to freedom outside the net once they have been counted. An estimated 100 are stored in a wine bin that Eric has already filled with clean seawater. These fish will be measured before also being returned alive.

Altogether, we count 587 bass. There are also some 200 mullet in the net, ranging from one to seven inches in length, as well as a few sand gobies and crabs. The latter are a nuisance because they often attack the bass; we get them out quickly.

Then it is back to the first creek with the net. On the way we try the west arm, but this is only showmanship, because we do not really expect the bass to go against the wind – and they don’t let us down. We get just three. Edward, who is taking notes, is suitably impressed. We then get on with the real business of the day, netting the eastern (with the wind) arm of the first creek. It usually produces more than the other creek, and again we are not disappointed. We get 1819 ‘0’ group bass and 35 second year bass of five to six inches.

The combined total of 2409 ‘0’ group bass marks this year class (1998) as very good one. Subsequent experiences with rod and line fishing in the lower estuary confirm that this is the case. We also see them again in the June of the following year, when we net 1702, a very good result for one-year-old fish.

Not all years produce on this scale. The purpose of this ‘0’ group sampling is to see how each year compares with all previous years. Most years since 1989 have been good, and a few, like this one, very good. There have only been two recent poor years, and both these were clearly attributable to adverse conditions. The most feared scenario is of finding a poor year class that cannot be attributed to adverse conditions. The presumed culprit in that case, would be over-fishing of the spawning stocks in the wintering areas. As yet it has not happened, but it could easily do so, because modern techniques for locating and catching bass shoals are so efficient. If it does happen, ‘0’ group sampling will give early warning. .

Finally a word of caution. If you ever get involved in this type of activity, treat the mud with respect. Most is negotiable in safety, but some is dangerous. One gets to know the nasty areas and avoids them. Remember too that permission is needed – from CEFAS for netting, and from landowners for access over private land. If the going gets tough in this often arduous, and sometimes discouraging activity, do not lose heart. Remember that you are at the ‘cutting edge’ in the management of the bass fishery. Among all the voluntary research activities that members now cheerfully undertake, none is more important than this.

Author: Donovan Kelley MBE

Historical note: This article first appeared in BASS magazine no.104 Winter 2002.

© Bass Anglers’ Sportfishing Society 2008