Other Seas, Other Bass by Donovan Kelley

It was my first visit to Buleji, a tiny fishing village out from Karachi, on the edge of the desert. With tent, camp bed and 2 weeks’ rations I had come to explore the fishing. After a year in the furnace heat of Upper Sind a welcome leave had been on offer. Others had followed tradition and gone north to the hills. I broke with tradition and went south to the coast for the sea breezes.

I had heard that there might be good sea fishing at Karachi. It was boat fishing, but I had a feeling that shore fishing would also be good, if I could find the right place. Our army maps had shown that at Buleji the sands gave way to a succession of rocky reefs. That, I felt, was the place, and now here I was.

My tackle was sparse and rudimentary. Just one stout 12-ft bamboo for beach fishing and a light 12 ft double-handed fly rod, shortened slightly, for the rocks. I tried the light outfit first, float-fishing with dead prawn. It was an immediate success with black bream (about 1 lb apiece) and the handsome yellowfin bream (about 3 lb). I had an indication of big fish presence when one of the bream was seized by a vague brown shape which rose from the depths briefly and dropped down again with the bream and my hook. “Gobra” said Ali, the village headman: rock-cod to me.

On the second day I tried the heavy outfit, casting out after dark from the beach at the head of the sheltered horseshoe cove where Ali and his men kept their boats. It was a warm night and the fishing was easy – no awkward cross-currents or surf. Ali said I would get only small fish in the cove, and results confirmed this: they were too small even to get hooked. He thought I would do better at Akpatthar, some way west of his village, or even from the beach where I had pitched my tent. I was on the point of packing when something undeniably big seized the octopus bait. It raced off seawards, taking 70 or 80 yards of line before I could stop it (and the bamboo was no soft touch). Several times it sheared from side to side of the cove, then we parted company. I wound in sadly to find the hook gone: the fine brass wire had kinked and snapped. Next morning I described the encounter to Ali. “Danthi” he surmised. I was none the wiser but vowed to find out. First however I had to seek Akpatthar, and I set off along the camel track westwards.

Ali had been vague about distance. Away in the west I could see the Kirthar Range of the Baluchistan hills, reaching the sea at Ras Muari. They looked 20 miles away, at least: I hoped I wouldn’t be going that far. Ali had said I would know it by the single small hut where the sands of a long curving bay ended in a rocky reef. Fishermen from Karachi occasionally used the hut. I tramped on steadily, thankful for the cool sea breeze. On my left the sands stretched endlessly, with no hut to be seen. I had been walking for an hour when on surmounting a slight rise I saw the bay some way ahead, and there was the hut, unexpectedly close to the water. It looked a perfect beach for my heavy gear, most promisingly at the near end where the sand gave way to rocks. It would be deep there.

Ali had been vague about distance. Away in the west I could see the Kirthar Range of the Baluchistan hills, reaching the sea at Ras Muari. They looked 20 miles away, at least: I hoped I wouldn’t be going that far. Ali had said I would know it by the single small hut where the sands of a long curving bay ended in a rocky reef. Fishermen from Karachi occasionally used the hut. I tramped on steadily, thankful for the cool sea breeze. On my left the sands stretched endlessly, with no hut to be seen. I had been walking for an hour when on surmounting a slight rise I saw the bay some way ahead, and there was the hut, unexpectedly close to the water. It looked a perfect beach for my heavy gear, most promisingly at the near end where the sand gave way to rocks. It would be deep there.

This however was just a reconnaissance and to save weight I had brought only the light rod and minimum gear. I had an hour off the rocks and found the black bream and yellowfins just as abundant as off Ali’s reefs.

On my return to Buleji, and mindful of the danthi which had defeated me the night before, I had another try in the cove. I quickly hooked – but lost – another goodish fish. Fears that I and my gear weren’t measuring up to these big fish were allayed however when another big one, which seemed to be well hooked, tore out to the mouth of the cove, then instead of swinging from side to side as the earlier one had done came straight back to me, faster than I could recover line; then went off again seawards.

These surely are typical bass tactics, I thought. Could it be..? For ten minutes the battle went on, with repeated powerful runs. Then suddenly it was all over and the fish, totally exhausted, came in on a small wave. Shining silver in the moonlight it was the most beautiful sight I could possibly have expected. Undeniably a bass, though rather different from the European one: thicker-set with a continuous single dorsal fin and less deeply forked tail. It weighed exactly 10 lb on my crude (25 lb X ½ lb) spring balance. Ali confirmed that it was a danthi.

Acting on Ali’s advice I next tried the beach in front of my tent. At once I hooked a fish which behaved very similarly – rushing seawards for 60 yards or so, then back to my feet; but then it turned left and headed for the reef. The line fouled on a rock and that was that: I wasn’t quick enough in following it. Next day I tried there again, and again the bass, as I felt sure it was, employed the same tactics. But this time I splashed after it as soon as it turned for the rocks and kept the line clear – to its downfall. It weighed 7½ lbs.

Six months later I came to Buleji again. This time I brought a bicycle to ease the three mile trip to Akpatthar. I went there three times and each time I had just one bass – never more, though I had less welcome stingray and rock-cod. The bass were again of good size, 9½ to 12 lbs. The Akpatthar fishermen were not there and getting the fish back to Ali was a problem one night when I had four fish totalling about 100 pounds. The problem was solved when, seemingly by some miracle, four of Ali’s men materialised out of the darkness carrying two stout poles. They slung two fish from each then set off in pairs with the poles on their shoulders.

How had they learnt of my need? Strange things happen in India, but I think Ali had realised that the conditions at the time might result in a good catch, and he sent them off to meet me and give me a hand back.

In a later visit I nearly had a rather different problem. I had hooked a huge sting-ray, probably 100 lbs plus, and I was quite unable to come to terms with it. It clung to the sand at the foot of the steep slope below where I was standing. It was quite impossible to budge it and its patience seemed unlimited. The stalemate lasted for two hours, then my patience gave out and I pulled mightily on the line. It was only about 20 lb BS and broke instantly.

Many of the large fish I hooked at Akpatthar broke away or simply threw the hook. Some were undoubtedly bass but most were probably rock cod. When hooked they made a fast beeline for the rocks – and nearly always got there. I never landed one over 30 lbs.

I had an extraordinary performance from a bass hooked off the beach in front of the tent. It leapt when hooked, then set off on the customary fast run seawards. After 20 yards it changed its mind and tore back to have a look at me. Not liking what it saw it tore away again, making for the rocks to my left. I followed as fast as I could and saw it weaving in and out of the tiny gullies, often with its back out of the water. By a miracle, and going in at times up to my neck, I managed to keep the line clear of the rocks. Eventually it ran out of water and stranded itself on the tiny patch of sand at the head of a gully. It was totally exhausted and weighed 10½ lbs.

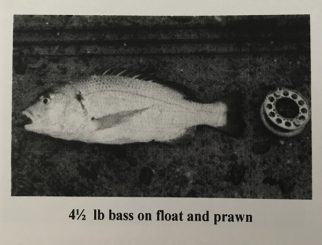

I found myself wondering what such tremendous fighters would do against my fly-rod. On my very last visit to Buleji I tried to find out. To the east of Ali’s village, beyond the reefs, there was a shallow sandy bay with rocks at the nearest end. It looked a likely spot for my experiment. I impaled a large dead prawn on a number 3 hook, set the small float to 7 feet and cast out. If 3 sounds absurdly small for a bass I can only agree. But hooks were very scarce out there in wartime, and rock-cod had cleaned me out of my modest stock of large ones. I prayed that any bass which came along would be a small one – a pious hope as so far all had been over 7 lbs.

The float had not been out many minutes when it went down. I struck and a silvery fish exploded three feet into the air. The fight that followed was no less explosive and lasted for nearly twenty minutes. My silk line was only 3 lb breaking strain but I had fortunately brought a landing net. With this I scooped out what was indeed a small (ish) bass of 4½ lbs.

The float had not been out many minutes when it went down. I struck and a silvery fish exploded three feet into the air. The fight that followed was no less explosive and lasted for nearly twenty minutes. My silk line was only 3 lb breaking strain but I had fortunately brought a landing net. With this I scooped out what was indeed a small (ish) bass of 4½ lbs.

Next day I tried again and hooked a similar fish which after another tense battle got off at the net. It seemed utterly exhausted but I let it go. Next day I saw it dead on the surface in Ali’s cove and retrieved it with my casting net. I was deeply moved by the discovery. How unfair that a fish which had fought so heroically for its freedom should be denied its reward. I had seen it happen before with yellowfin bream lost at the last minute. This never happened in Britain: why did it happen here? Was the sheer ferocity of the battle too much for them, in these warm seas? Had I been fishing too light? As this was my last visit to Buleji I had no chance of putting the possibility to the test. Years later, bass fishing in Anglesey with a light trout spinning rod, I found myself wondering again whether it was possible to fish too light. The “Light Caster” was handling the 3 and 4 pounders well but then I hooked a bigger one and the situation transformed. Knowing it could be big I had glanced at my watch when I hooked it. It was fifty-five minutes later that I eventually eased it onto the sand. Too long I felt: unfair to the fish and wasteful of my time. I never fished so light again, for bass: the “Light Caster” has remained unused in my tackle cupboard since then.

To my regret I never positively identified those Arabian Sea bass. I was in touch with the Bombay Natural History Society and I had a copy of Day’s monumental “Fishes of India”; so there was no excuse. But I had other preoccupations and never got down to it. It would have been nice to know to what size they grow – and, in those warm water: how fast. I could readily visualise them topping the 20 lb mark, so elusive in Britain.

From ‘Life with Bass’ by Donovan Kelley