CHAPTER 2 – TECHNIQUES – BAIT FISHING

Surf Angling For Bass In Cornwall

The magnificent county of Cornwall offers the bass angler many opportunities. From over 200 miles of craggy, heavily indented coastline, interspersed with many fine beaches and estuaries, almost every type of bass fishing technique is possible. The geographical location of the Cornish peninsula means that it is a particularly suitable habitat for bass, with many of its estuaries now known to be nursery grounds for the species.

To describe the many places and methods of catching bass from Cornish waters might require a whole volume, so the intention of this article is to concentrate on my own preference, surf angling, in the hope that it will help you to fish the Cornish beaches, or that maybe some of my techniques can be applied in other localities. The Atlantic surf is, to my mind, absolutely fascinating and it is that aspect of bassing that has drawn me for the last thirty years.

Where to fish

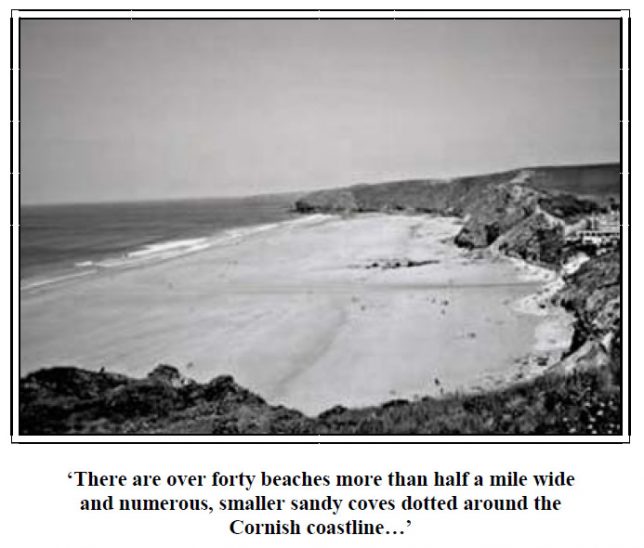

There are over forty beaches more than half a mile wide, and numerous sandy coves dotted around the Cornish coastline, so there is a wide choice of venue. It pays to visit a few likely places before deciding where to fish. This is not as troublesome as it may seem, because several beaches can be quite close together. It is worth spending some time searching for a good surf so perhaps a short digression on what to look for might prove helpful. The Cornish peninsula is exposed to the prevailing westerly winds and on most beaches facing this direction a surf will be produced under certain conditions. Local variations are frequently encountered – on the north coast, west and northwesterly winds tend to be best, while on the south coast (other things being equal) southwesterlies undoubtedly fish better. However, the most important factor for the best bassing conditions is the presence of Atlantic swell, i.e. an even surf with deep water tables. Storms, usually associated with troughs of low pressure that occur well out in the ocean, generate these waves that arrive in regular sequence after travelling some hundreds of miles. These can occur with little or no local wind. On the north coast in particular, it is possible for a slight swell to be ‘lifted’ by a strong offshore, (i.e. south or southeasterly) wind blowing into it, thereby producing a marvellous surf. Looked at from high cliffs, the swell (or ‘ground sea’ as it is also known) is seen as dark bands on the surface of the sea running parallel to the shore.

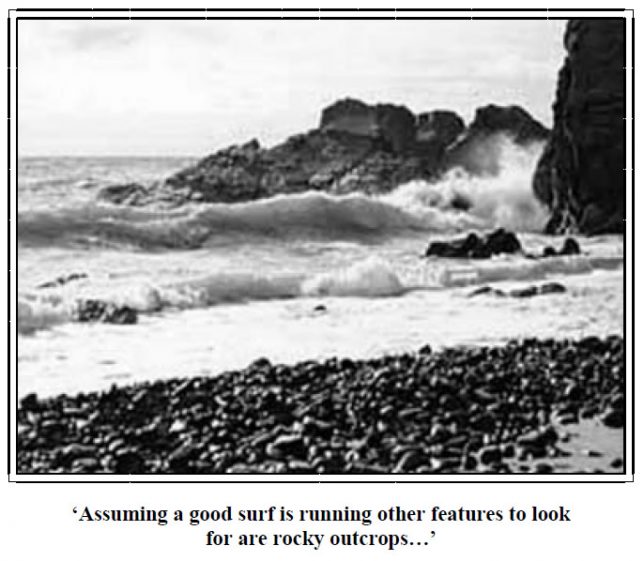

The likelihood of contacting swell is greater on the more exposed north coast, and therefore the best bass beaches tend to be found there. Specific recommended marks include Widemouth Bay (near Bude), Constantine Bay (not far from Padstow), Watergate Bay (Newquay), Perran Sands (Perranporth), Hayle Sands and Sennen Cove (near Lands End). Some beaches, such as Hayle, are up to three miles long and so some thought must be applied in selecting exactly where on the beach to fish. Assuming a good surf is running, other features to look for are rocky outcrops, gullys, and streams running across the beach. Gullys usually occur around the low spring tide mark, being scoured out by continuous wave action at this point. Being slightly deeper than the surrounding flat sands, they are natural food traps and are always worth locating. The attraction of fresh water to bass is probably the reason why I have frequently caught them where a stream runs into the surf.

The likelihood of contacting swell is greater on the more exposed north coast, and therefore the best bass beaches tend to be found there. Specific recommended marks include Widemouth Bay (near Bude), Constantine Bay (not far from Padstow), Watergate Bay (Newquay), Perran Sands (Perranporth), Hayle Sands and Sennen Cove (near Lands End). Some beaches, such as Hayle, are up to three miles long and so some thought must be applied in selecting exactly where on the beach to fish. Assuming a good surf is running, other features to look for are rocky outcrops, gullys, and streams running across the beach. Gullys usually occur around the low spring tide mark, being scoured out by continuous wave action at this point. Being slightly deeper than the surrounding flat sands, they are natural food traps and are always worth locating. The attraction of fresh water to bass is probably the reason why I have frequently caught them where a stream runs into the surf.

There are one or two other points to consider before finally deciding when to fish. Personally, I prefer to fish in daylight because part of the magic of surf angling in Cornwall is the superb, rugged scenery. However, in July and August the presence of holidaymakers means that the only practical options are a very early start or night fishing. The latter is usually my preference, because the high atmospheric pressure at that time of year means little or no surf is present anyway, and such conditions might produce havens of sandeel or brit activity with the chance of a bass feeding frenzy.

The best conditions are usually met with later in the year, as during the autumn the frequency of Atlantic depressions increases, producing the classic surf for bass fishing.

Very high waves may be produced when oceanic swell reaches the shallow waters of true surf beaches and this, unfortunately, also attracts another species to the shoreline – surfers! Their season now extends well into autumn, so it pays to avoid their known spots or, again, switch to night fishing.

Tackle and baits

The tackle for surf angling allows a wide choice of personal preference, although I would not recommend going too heavy. Besides the sporting angle I have found that light tackle will hold in a strong surf, where at first glance this may not seem possible. This is because strong lateral currents are not usually present on surf beaches (except perhaps near promontories or in rare cases, where riptide is encountered).

After trying several combinations my preference is for a rod capable of casting three to four ounces with a length of about eleven and a half feet, coupled with a small level-wind multiplier. Line strength of about 10lb breaking strain with a shock-leader of 20 to 25lb is about right, although a friend has successfully used fifteen pound line right through so avoiding weed being trapped around the leader knot. Note. Powerful casting is not necessary, and indeed can place the bait beyond the fish.

Only one hook is necessary, and to avoid tangling in the surf a paternoster with a short snood is best. I use bronzed hooks in sizes 1 to 3/0 depending on the bait size and type, but the most important factors are that the bait is presented without tangling and that the hook is needle sharp and protruding from the bait.

After examining the stomach contents of many bass caught in the Cornish surf I have found that their food consists mainly of sandeels (about 50 per cent), crabs (about 35 per cent) with the remainder made up of shrimps, small fish and sand hoppers, etc. The hardbacked crabs found in their stomachs are mainly small (1/2” – 1” across the carapace), the sandy coloured swimming variety. Sandeel is therefore, undoubtedly, the best bait for Cornish surf bass and it is best obtained by scraping (or ‘Vingling’ as it is locally known) at low water. I use the back of a long filleting knife but a proper tool, rather like a long bladed screwdriver with its end hook-shaped, can be easily made or purchased locally. Caution: beware of the stinging weever fish – a useful tip is to wear a thick glove on the collecting hand.

An inferior bait, although if fished properly a reasonably successful second best, is blast-frozen sandeel. Don’t bother with frozen sandeels that look yellowish in the packet, as these will probably be slow-frozen and are quite useless as bait once thawed. Other baits on which I have landed bass from these beaches include lugworm (especially good at night), razorfish (difficult to obtain locally), mackerel strip (cut to resemble sandeels) and soft crab. There are few places to dig lug but the exposed upper reaches of estuaries (such as at Looe) can usually be relied on.

Live, or freshly dead, sandeel is fished by passing a smallish hook (say 1 or 1/0) through the mouth and out of the gill slit and then nicked into the back a short distance behind the head, or nicked into the belly. When using this method a fairly gentle cast with a flexible rod ensures that the eel stays on the hook. If a frozen eel is used I prefer to mount it with a baiting needle, or to mount it by inserting the hook 2/3 along the eel, and with a slight curving motion, bringing the hook point out at the mouth.

At certain times (especially on night spring tides in the summer). Large sandeel shoals may be close inshore. Walking across the sand and in the shallows at low water may disturb them and, on the odd occasion they may actually be seen to emerge from the sand. Then bait collection will be easy and the bass will almost certainly be very close in.

Technique

Technique

A good surf is definitely needed on these beaches for daylight angling, because the attraction for the bass will be the food uncovered by the pounding breakers. Bass undoubtedly revel in this well oxygenated water and the tumbling waves also offer them some protection against predation by the seals that are present in Cornish waters – more-so on the north coast.

Fishing in daylight in very clear water and no sand being disturbed will result in few, if any, bites. I have found the best time to be just as a blow is starting, especially if it follows several days without surf. If it is not too rough, spring tides are usually more productive than neaps. On Cornish beaches the best period to fish is generally the two hours either side of low water, but when conditions are right they may be caught right up to high water.

A cast of fifty to eighty yards is normally sufficient, as around low water one is generally directly over sandeel habitat and there is no point in casting beyond it. The bass will naturally be expecting to find sandeels here and therefore this is where the bait should be placed.

Weed can be a nuisance, and at times so much is present that it can be completely unfishable. If this is the case a move is the only answer. However, it often only collects in the gullys around low water, and sometimes the flooding tide may leave this weed behind in them. When this happens, under otherwise good conditions, the bass may then be caught higher up the tide in the clearer water.

Bites and landing the fish

Missed bites can be a problem in the rough and tumble of the surf. To strike or not to strike, or indeed whether to hold the rod at all, has been debated many times. My method, which has been well tested by others, involves the use of a breakout lead and results in fewer missed bites. After casting the rod is set upright in a monopod rod rest and the line is tightened until there is very little slack. The flexible tip then bends towards the weight and will be seen to follow the plucks of the wave crests. This rig is self-hooking – a taking bass is pulled up with a jolt because of the grip lead and the short, fairly inflexible snood. The method is best suited to a light flexible rod and the hook must be needle sharp. Heavier tackle will not give to the pull of the surf, resulting in the lead dislodging and a slack line which can result in a tethered fish and no indication of it.

There are basically three types of bite indication when using the rig described earlier. The most common is a jagged lunge of the rod tip that generally materialises into a schoolie. Another is when the rod bends and stays keeled over, which usually means a fish better than a schoolie. If the tip suddenly springs upright, this means a fish is running inshore or, more rarely, the bait has been snatched but the hook is missed.

A bass hooked in the surf will often swim parallel to the beach, but whatever happens contact must be maintained through a tight line. Bass usually struggle more in the last few yards when they feel the sand beneath them, and with the effect of backwash a fish might well be lost unless beached carefully on a following wave.

Warning

Due to the exposed nature of most of these beaches it is well nigh impossible to fish in gale force conditions. In fact on the north coast this can be quite stupid as, in combination with a spring tide, very dangerous conditions can ensue. One moment the sand is dry and the next a table of water perhaps four feet deep can surge up the beach and knock one over. In any case the backwash from a powerful surf will draw the sand from under your feet. In winter, especially, I have seen surges such as this of up to one hundred yards on flat beaches. If there is a forecast of more than about Force Six accompanying a big tide, fishing a more sheltered spot should be considered.

I don’t recommend fishing alone at night in the more remote places unless you are familiar with the area, because some Cornish beaches have deep potholes and very soft sand to trap the unwary. Finally, this kind of angling can also be very tiring as the distance from the high water mark to low may be several hundred yards on flat strands. This means that one cannot fish for long in one place, particularly during the ebb and flow of a spring tide.

Author: Nigel Hester

Historical note: This article first appeared in BASS 31 and BASS 32. For reasons lost in the mists of time these two magazines were published as a joint Spring/Summer 1984 issue. The original article is subtitled A BASS ‘Catchers Handbook’ Supplement, and may also have been issued separately from the magazine. It was republished in BASS magazine no.115 Autumn 2005.

© Bass Anglers’ Sportfishing Society 2008