CHAPTER 5 – GOOD DAYS, BAD DAYS

Taking Breath, And Having Your Breath Taken Away

It is the belief of some that life should not be measured in the amount of breaths taken, but the number of times your breath is taken away. It is still before 6.00am and twice already, the sights I have witnessed have induced momentary respiratory arrests.

The first occurred one and a half hours ago. After silently sliding my small boat out of harbour in the tail of the night, I looked behind to see a near full moon sinking behind the sleeping Cornish Village: a monochrome of lunar highlights on slate roofs, dark hills, and inky water. All was motionless except for my unfolding moonlit wake. Many times from this spot I have looked back and admired the sight of this community clinging to a headland, but to observe the scene at night was new to me; the different illumination on familiar structures and the absence of human activity had a great impact on me. I stared in admiration at the breathtaking scene for over a minute – a mighty sacrifice of time given my urgency to pursue bass.

An hour after leaving port, having arrived at ‘my’ mark, and anchoring in a fast run of tide, my breath was snatched for the second time. The August sun had yet to emerge as I observed the eastern horizon slowly ignite between each cast of my lure. A solitary commercial boat emerged from behind a headland as it plodded towards the reef. His presence, like mine, not driven by insomnia but by the knowledge of the potential rewards of fishing spring tides at high water, in low light. Normally I am blind to the aesthetic qualities of a craft if I know it to be piloted by someone whose reward for catching bass is financial. Perhaps my loss of sleep had softened my judgement. Yet the dark outline of hull, wheelhouse and outriggers, against a smouldering gull-dotted sky, right in line with the point where the sun emerged over the horizon, was the finishing touch to an inspiring image.

It’s now 10 minutes on from sunrise and the fishing has been unproductive except for one near miss. With my competitor now fishing in the area, I have decided to up anchor and relocate to where the flooding tide rips between a brace of huge rocks. These stranded outcrops, like icebergs, only reveal a small portion of their mass above the waterline. Of all the fishing marks in this area I feel it has the most potential. Yet it is the one most likely to hole a boat, and my lack of familiarity with the topography kept me from fishing here in the semi-darkness. The two great stones mark the summit of a steep shelf rising 20 metres from the otherwise featureless seabed. Fishing here is more like casting into a spate river than the open sea, given my river fishing upbringing it is of little surprise I am called to such places.

I manoeuvre the boat with great care. Reconnaissance of the spot yesterday led me to believe that at this state of the tide I have 3-4 feet of water below, but the reef’s fearful reputation keeps me from being complacent. A book on Cornish wrecks revealed the extent of the carnage in this area over the centuries. The very rocks before me are relatively minor players compared to those guarding the outer reaches of this reef, having claimed ‘only’ 11 vessels, yet the loss of life here is still measured in three figures. It takes a few minutes for images of the outstretched hands of drowning mariners to sink to the depths of my mind. Yet once the anchor is set and I pick up my rod all awareness of doomed sailors, setting moon and rising sun is eclipsed by the spell of fishing. All that remains is a strip of sea between me and the rocks towards which I aim my lure, as I seek to conjure a bass from beneath the water’s veil.

Times such as this, when fishing becomes all engrossing, refuting the romantic notion that escape to the water is undertaken to contemplate life. Yet to tell non-angling friends when I am fishing, all I think of is fishing, would probably destroy the one aspect of the activity that makes my obsession intriguing to them.

After only a dozen casts I was rather pleased to come up with a solution to catching – unfortunately my self – satisfaction was short lived, as I failed to find the answer for landing. After a one minute tussle the fish (surely a bass by the way it fought) came free without obvious cause.

Despite an outcome many might consider a failure, the incident is a cause for joy not sorrow. It is the first time I have fished this specific mark and I now know two things: at least one fish has moved through the area, and the plug I am using, if not exactly the right one, is not completely the wrong one.

My first cast to another spot is misjudged and moulded plastic bounces on stone. I wind quickly and impart two fast twitches on the rod and the lure is snatched violently. The initial run is frantic, amplified by the strong tide. Unfortunately an over tightened drag following my earlier tussle results in no line being given. Panic afflicted fingers vainly struggle to make the adjustment, as rod and braid are subjected to forces I am sure will destroy one of them. To my amazement it is the fish, and not rod or line that yields. As often happens in battles where the fish is prevented from gaining line on the first run, their resolve quickly breaks if the line holds. Soon my hands pull the bass from the water into the boat.

My first cast to another spot is misjudged and moulded plastic bounces on stone. I wind quickly and impart two fast twitches on the rod and the lure is snatched violently. The initial run is frantic, amplified by the strong tide. Unfortunately an over tightened drag following my earlier tussle results in no line being given. Panic afflicted fingers vainly struggle to make the adjustment, as rod and braid are subjected to forces I am sure will destroy one of them. To my amazement it is the fish, and not rod or line that yields. As often happens in battles where the fish is prevented from gaining line on the first run, their resolve quickly breaks if the line holds. Soon my hands pull the bass from the water into the boat.

Lying flank up between my palms, the weight of the body causes the midriff to sag pleasingly towards the floor of the boat. The morning light is scattered by the impact against scales as the boat swings on its anchor. A cavernous mouth gasps for water yet all the creature can take in is the soft morning air. It is however, the dimensions as well as her aesthetics that takes my breath away for the third time in less than two hours. Although the fish is far from being a monster as defined by record committees, it is by far the largest Cornish bass I have seen, let alone held.

Lacking scales I assess the length against a measure painted on the rod. The fish is just short of the 29-inch mark (say 73cm). The bass is quickly returned to its own dimension and swims away into my memories.

Keen for further success, yet wishing to maintain high rewards for any captures, I swap my factory—made diving lure for a homemade surface plug.

The tide is now nearing its peak. The next dozen casts produce four fish between 4 and 5lb, with even the ‘unsuccessful’ casts inducing attempts to hit the balsa plug from good-sized bass. Success in Cornwall on surface lures has been rare for me. Given the magnitude and frequency of the splashes of the fish at the lure I hypothesise the reason for the low ratio of hooked fish compared to number of attacks — could be the bass’s lack of practice of this type of ambush, or a somewhat cautious attack at the lure? The real explanations I suspect are far more subtle; like my plug on the smooth water, I’m only scratching the surface.

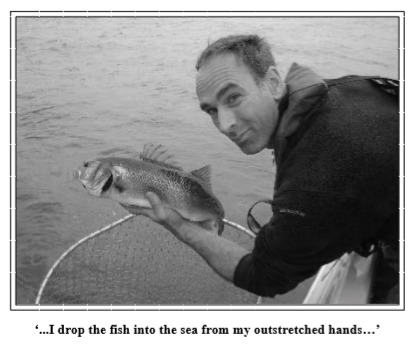

The commotion has alerted the commercial catcher, who makes a close pass to inspect what I am doing. Certain he has seen me catch, I make a big show of returning what to him is just a ten pound note — treasure I only wish to borrow from the ocean. As I drop the fish into the sea from my outstretched hands I look towards him. He shakes his head in disbelief. The body language I recognise as a mirror of my own when seeing a bass thrown into his fish box.

The commotion has alerted the commercial catcher, who makes a close pass to inspect what I am doing. Certain he has seen me catch, I make a big show of returning what to him is just a ten pound note — treasure I only wish to borrow from the ocean. As I drop the fish into the sea from my outstretched hands I look towards him. He shakes his head in disbelief. The body language I recognise as a mirror of my own when seeing a bass thrown into his fish box.

Annoyingly he continues to observe. Keen to hide my methods I remove the surface plug using the gunnels for cover. I clip on a neglected spinner from the depths of my lure box and cast away from the rocks into open water.

After ten minutes of watching me fishing “my” water, whilst trolling his sandeels, he heads away. He knows I am trying to hide my hand, yet he has money to make and chugs off to his favoured ground several hundred yards away. His surveillance has caused me to lose precious minutes of prime fishing time in these waters, but keeping my methods secret from the commercial boats is paramount. Passing on knowledge of effective methods and exact locations can only be detrimental to the local bass population.

As I watch him retreat I recall a notion of mine – one that began as a half baked idea borne from daydreaming, but one that grows on me with the passing of time and further reflection. The theory is this:

Angling has repeatedly shown that fish, if given a chance, modify their actions in response to past events. For example, Pike in trout reservoirs quickly become difficult to catch on lures after a week or two of huge catches, when the pike fishermen are first allowed on a water. Trout are also widely reported to be harder to fool following the introduction of catch and release. In both situations subtlety and innovation becomes increasingly important to bring the angler success.

It is not only first hand experience that leads to modification of behaviour. Laboratory experiments have shown that fish, when faced with an unfamiliar meal, ignored it until they ‘learn’ that it is food by being shown a video of a fish eating such food. Obviously the ability to change responses varies between individuals in a population of fish, a notion supported by frequent accounts of anglers repeatedly catching the same fish (often on the same day).

Based on the above, I believe that if I can be one step ahead of the commercial rod and line fishermen in terms of innovative techniques, I continue to practice catch-and—release, the fish I catch will be a little more wary when confronted with the tackle of a commercial rod and line fishermen and less likely to be caught.

Obviously the method is far from 100 per cent effective, and even if I am merely clutching at straws, there is a slight possibility that these combined practices can make a small difference to some fish, which in itself adds to the pleasure of watching a bass swim away.

With the commercial boat now far enough away I recommence fishing but it is apparent after a few dozen casts with three different lures that the sport here has died. The change could be due to the increased light levels, the now falling tide, or the disturbance from the commercial boat and its throbbing diesel engine. Whatever the cause I am not unduly concerned — the next morning flood tide will be another opportunity.

Time spent fishing is the filling sandwiched between anticipation and recollection. I will be back home in time for breakfast, before wandering down to the beach with my family to enjoy another blistering day. Between playing cricket and building sandcastles with the children I will laze in the heat, plotting tomorrow’s dawn raid and recalling this morning’s breathtaking events.

Author: Matthew Spence

Historical note: This article first appeared in BASS magazine no.112 Winter 2004.

© Bass Anglers’ Sportfishing Society 2008