The Fishery Scientists, Pawson and Pickett by Donovan Kelley

It was Sunday morning and the little Welsh town had not yet woken up. As I walked along the main street there was not another soul in sight – until the smart young lady emerged from a side street and asked where she could get some milk. I was going the same way and we walked on together. She, I learnt, was on holiday with her husband. I told her I was on one of my regular short visits for the bass tagging programme. Expecting just a conventional polite response to this information I got a real shock. Her husband was a marine scientist at the Burnham shellfish laboratory and would be transferring shortly to Lowestoft to work on bass with Mike Pawson. It was another of the remarkable coincidences which have illuminated my fishing life.

I knew that Lowestoft was about to increase its commitment to bass research and was delighted to be brought in touch so early with one of the main actors on the research scene. Graham Pickett and Diana joined me that evening for a drink, and Graham later came on the rocks at the river-mouth for some tagging.

It was the start of a long – and for me instructive and inspirational – relationship in our mutual involvement with bass: Graham a trained professional scientist but constrained by Ministry policy and resources, I an amateur but proud of my independence and anxious to demonstrate the integrity of my work on bass,

That was seventeen years ago. Since then Graham has been a regular visitor to my home in Cornwall, often with Mike Pawson, the senior partner in the bass work at Lowestoft. Every aspect of the bass scene is discussed, gaps in knowledge identified, projects planned, progress reviewed, problems addressed. In those early days there was much to be done which was outside my competence, including laboratory work with expensive equipment and costly cruises in research vessels to obtain eggs and larvae of the newly-spawned young bass. But much of the fieldwork – like tagging and nursery sampling – was suited to amateurs working on a voluntary basis; so was some of the indoor work, like scale-reading – and the inevitable deskwork that seems to follow from all research: drafting reports and papers, and an ever-increasing correspondence.

Right from the start it was apparent that Mike and Graham were cast in different mould from Mike Holden; notably that they were willing, indeed anxious, to listen to the experiences and views of one who, though not a trained scientist, had long been fishing for and studying bass. At the time of that first chance encounter I had been tagging for ten years on the west coast, in Anglesey, Pembrokeshire and North Cornwall. It had been found in each case that bass tagged in summer moved to the waters of the western English Channel for the winter, returning to their respective summer areas each summer.

Right from the start it was apparent that Mike and Graham were cast in different mould from Mike Holden; notably that they were willing, indeed anxious, to listen to the experiences and views of one who, though not a trained scientist, had long been fishing for and studying bass. At the time of that first chance encounter I had been tagging for ten years on the west coast, in Anglesey, Pembrokeshire and North Cornwall. It had been found in each case that bass tagged in summer moved to the waters of the western English Channel for the winter, returning to their respective summer areas each summer.

I had felt for some time that it would be interesting to apply the reverse checks – tagging in winter at a place in the western channel where bass were known to congregate in winter. Mike and Graham felt the same and took action, tagging In October at the Runnelstone off south-west Cornwall. Of the twelve recaptures that followed 3 occurred later in the same winter in S. W. Cornwall, the other 9 at various points on the west Coast in the next two summers – 1 in N. Cornwall, 1 in N. Somerset, 5 in S. W. Wales, 2 in N. W. England. It was the perfect complement to the summer taggings and confirmed that the conclusions drawn as to the seasonal migrations were correct.

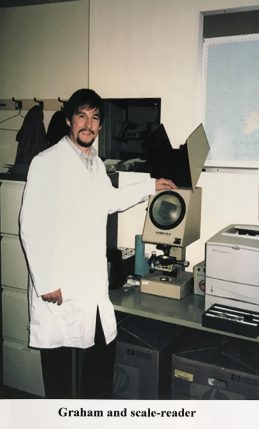

Other tagging work followed, including topping-up a study off Essex in which Bob Cox and other charter boat operators had been tagging the bass caught by their angler-clients, while I kept the records and read the scales. In his follow-up scheme Graham on one occasion while out with Bob caught a bass of 15 lb 14 oz. Most unfortunately Bob had used up all his film, so a very fine bass went back tagged but unphotographed. As a next-best Graham has provided a laboratory shot, alongside his sophisticated scale-reader. The Essex work, and a follower by Graham at Portland, established that south coast adult stocks were subject to much the same migration pattern as those of the west coast; the bass moving west down the Channel for the winter and returning in summer to their respective areas. One of the Portland fish, a 13-pounder, was recaptured in winter off Santander in northern Spain.

It had become apparent that the adult bass had a very systematic seasonal migration pattern. For juveniles, many of which had been tagged in the adult schemes, the pattern seemed much more haphazard. To clarify the picture the tagging effort switched in 1982 to immature fish under 6 years old. Graham has tagged several thousand in the important Hampshire nurseries and will be publishing the results of that and other juvenile taggings shortly.

Tagging however, though important, is only a small part of Graham’s research effort. With Mike he is responsible for advising the Minister on the management of the bass fishery; in particular, for identifying and recommending the most appropriate protective measures for maintaining the numerical health of the bass stocks. To do this they have to strike a balance between two very important, but conflicting, aspects of the bass scene: the quality of each year’s spawning and of 0-group survival through their first critical winter; and on the other hand the losses due to fishing at various stages in their development. Natural mortality through e.g. predation by large fish and mammals also comes into the reckoning but does not with bass appear to be at a significant level.

Most recent years have produced good spawnings (and good winter survival). But fishing pressure has been increasing – particularly by gillnetters in the nursery estuaries, where by the late 1980’s first-year recapture rates were reaching dangerously high levels (in at least one, over 60%). Clearly special measures were needed urgently to arrest this trend. In 1986 Mike and Graham produced a detailed report on the state of the bass fishery and its exploitation. They recommended an increased size-limit, a minimum mesh size for nets and closure of designated nursery areas. A MAFF press release gave details of the proposals and invited comments.

That was where Mike and Graham entered what was probably the most exhausting and frustrating phase of their work. They had for years been getting details of commercial catches from the Ministry’s fishing inspectorate. They had also had talks with fishermen and anglers and their representative bodies. Now they had to meet them – in their respective areas – and consider their objections to the proposals. Fishermen do not like being restricted, and most tend to look to present needs rather than to the longer-term viability of their fishery. Mike and Graham had to deal with a lot of ill-informed resistance to their proposals. They knew that failure could presage a fishery disaster comparable to that caused before the war by the gross over-fishing of the herrings. Anglers were more conservation-minded and wanted even stronger measures including a higher size-limit; but they too had reservations as to the practicability of the nursery closures.

The negotiations that followed were protracted and sometimes acrimonious. The fishermen had a vociferous lobby whereas anglers were weakly served. The recreational fishery was believed to be of greater economic value than the commercial fishery (this was later confirmed by a special study); but anglers are not good at paying for proper representation at the top level. In that climate fishermen gained concessions over the original proposals which were later seen to be misplaced.

It was a measure of the difficulties in getting a compromise reasonably acceptable to both sides that nearly four years passed before the measures got on the statute-book. Though not quite as strict as originally hoped it was a good package, and the benefits were immediate. For two years there was a very good observance level and stocks, notably of the highly abundant 1989 class, benefitted.

There was however a serious omission, one which was outside Mike’s and Graham’s competence: a complete lack of funding to meet the cost of enforcing the new provisions – something which did not require statutory provision and which should have been dealt with at administrative level. Fishermen and many anglers were not slow to note the omission and to act accordingly. In many nurseries there is now exploitation by netters and anglers at the pre-regulation level.

There were other features of the regulations which left something to be desired – e.g. badly sited nursery boundaries, omission of important nurseries, loopholes in mesh concessions. In 1995 Graham, with authors concerned with the economics of fisheries, produced a report reviewing the effects of the regulations and indicating ways of strengthening them. In 1997 MAFF made proposals to implement the main features of the report which are now under consideration. Regrettably, the enforcement problem is not dealt with.

Much of Mike’s and Graham’s work on bass has been the subject of papers in (chiefly) the Journal of the Marine Biological Association. In 1989 Graham had a paper on bass published in “Biology”, in that publication’s Exploited Animals series: it was a marvellously concise review of the bass scene which became the perfect starter for students commencing work on bass (one of them seems to have kept my copy!).

In 1995 the final word on the bass and its fishery appeared: “The Sea Bass: Biology, Exploitation and Conservation”, by Pickett & Pawson, 337 pages. It gives full coverage to the recreational side of the fishery, as well as to the commercial. Fittingly, in view of his major part in the compilation, Graham’s name comes first in the authorship credit. Betty and I were astonished to see that we had been honoured in the dedication. It was so unexpected I was unable to find my voice for several minutes, to tell Betty.

The final Word? In fish research nothing is ever final. Graham told me, when the book appeared, “it’s already out of date”. That was an exaggeration, but the fish scene can indeed change quickly. The unprecedented experience of 8 good spawnings out of the last ten won’t go on forever – especially if the recent tendency towards a return to cooler winters continues. Exploitation levels can change – and are changing, for the worse: the heavy winter-area killing by mainly F rench pair-trawlers is getting heavier (5,000 tons reportedly, last winter). Perhaps worst of all is the failure to enforce the nursery regulations. Mike and Graham are working on these problems, which however are more appropriate to politicians than to scientists.

From ‘Life with Bass’ by Donovan Kelley