The Influence Of Year-Class Strengths by Donovan Kelley

I am sometimes asked, “why is there such a conspicuous gap in the range of sizes I am catching?” The enquirer has been getting plenty of young adults in the 1½ to 3 lb range, and odd good fish of 6, 7 or even 8 lbs. But nothing in between. The missing sizes were what he has normally found dominant in his bass catches. Where were they?

The answer of course lies in the variations which occur in the abundance of different year-classes. In that example (a recent one) the smaller ones were bass of the highly abundant 1989 and 1990 year-classes (with some 1988’s – also a strong class, though patchy). Immediately preceding those classes were three very poor ones: 1985 and 1986 failures, 1987 little better. Before those three however were three good ones: 1982, 1983 and 1984. These provided the larger fish. The “missing” 4 and 5 pounders were the non-existent products of the three dud classes in between.

With the superabundant 1959 class the effect was even more dramatic. When it first manifested itself as an exceptional class, in 1967, inshore catch-rates rose immediately to the level of the early postwar years – and stayed there for three years. They would have gone on much longer but for the misfortune of two total failures (1962 and 1963), and two very poor classes shortly after (1965 and 1968).

With the superabundant 1959 class the effect was even more dramatic. When it first manifested itself as an exceptional class, in 1967, inshore catch-rates rose immediately to the level of the early postwar years – and stayed there for three years. They would have gone on much longer but for the misfortune of two total failures (1962 and 1963), and two very poor classes shortly after (1965 and 1968).

With four duds over only seven years fishing standards could have slumped to the lowest ever. They were saved by the 1959 class. The extent to which that class dominated catches through the early 1970’s – and saved our Anglesey tagging project from ruin – was apparent in the steadily rising average size of the adult bass we tagged: from 3¼ lb in 1971 to nearly 5 lb in the final year 1975 – with a further rise to near 6 lb in the 1977 follow-up.

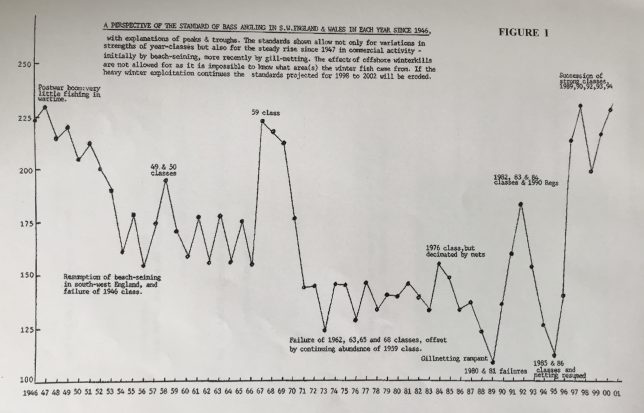

The very considerable influence which year-class fluctuations can have on our catches is still not as widely recognised as it should be. We tend always to blame over-fishing as the sole cause of disappointing results. Important though over-exploitation is – and it is certainly that, and getting worse – it is far from being the only influence on catches. In an attempt to demonstrate the year-class influence I have plotted the quality of bass fishing available each year since World War II, in South-West England and West Wales (Figure I). It uses an “index” of the relative numbers present each year at ages 8 to 17 for each of the year-classes concerned. The index is derived from abundance data in two published papers*, and from further unpublished data for more recent years. It assumes a basic value of 10 at age 8 for each class, falling by 1 each year to a value of 1 at age 17. This basic rate is used for very weak classes which are not total failures (those get no marks at all, of course). For a slightly better class (but still not good) the values are raised by X 2. For a moderate class, X 3. For a good one – e.g. 1982, 83 and 84 – X 5; and for an outstanding class X 10. Only two qualify for this last: 1959 and 1989. Six classes get no marks – 1946, 1962, 1963, 1965, 1985 and 1986. Each index is an arbitrary figure, telling nothing by itself but giving a useful means of comparing fishing standards in different years: i.e. of the level of bass presence in the years to which the classes contribute catches.

Take a look at Figure 1. Remember that the years are fishing years, not year-classes. The standard used, on a scale of 0 – 250, is as stated meaningless by itself but useful for comparing the quality of fishing from year to year. For a standard below 100 – to which mercifully we have as yet never descended – bass fishing would not be worth anybody’s trouble. A standard between 100 and 150 means fishing is poor – and not worth a busy man’s trouble. Between 150 and 200 fishing will be quite good; over 200, very good. This last has been reached only twice – for a short period after the war and for again a short period after the 1959 class burst on the angling scene. But it should happen again over the next few years thanks to a succession of good spawnings since 1989.

Don’t worry about the method used. I know it is sound for adult bass fishing in south-west England and West Wales – and may have limited application elsewhere. But DO worry about those years of the immediate future. The accident of an unusual succession of good spawnings has given us a wonderful opportunity to get bass fishing standards restored to the very highest level, as it was in 1946 to 1952 and again 1967 – 69. It is an opportunity we neglect at our peril. It may never occur again.

Everything depends on how effectively we address two serious problems in bass protection. First, the nursery regulations need to be ENFORCED. After the first two years they received scant attention, and in some estuaries netting is back to the level it was before 1990. Second, something needs to be done about the grossly excessive exploitation of adult bass in the west Channel wintering area. At the very least, catches need to be REGULATED. Both are political issues: the scientists have done their stuff and it is up to the angling world to pressure the politicians.

* Bass Populations and Movements on the West Coast of the UK (Table 16, JMBA 1979) Age Determination in Bass and Assessment of Growth and Year-class Strength (Table 6, JMBA 1988)

From ‘Life with Bass’ by Donovan Kelley