The Life Cycle Of Bass

For anglers interested in the biology of bass, the Bass Anglers Sportfishing Society (BASS) has produced this brief note on the life cycle of bass in UK waters, drawn from information* available at the time of writing (February 2021). This note also appears in BASS Magazine 170.

Early years

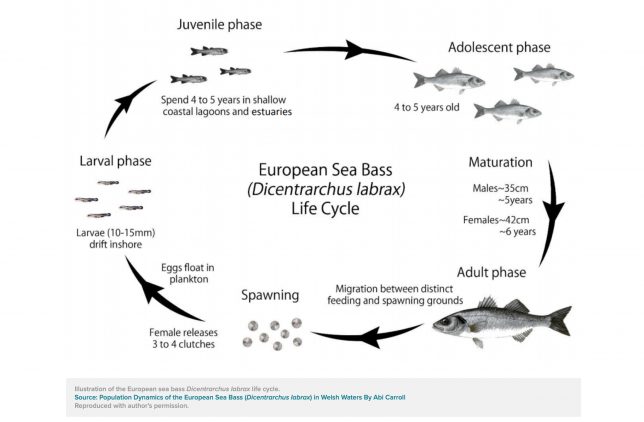

Bass spend the early years of their lives mainly in or near their nursery estuary, usually moving out for the winter. In their adolescent phase (5-6 years), bass wander widely and apparently at random, adopting at the end of this phase the area for their future summer life.

Adulthood

Upon reaching sexual maturity at age 5 (males) or 6 (females), bass enter their adult phase (scientists call this “recruitment” into the mature bass biomass). They spend each summer and early autumn on the same inshore feeding grounds, exhibiting socalled ‘site fidelity’. The oldest bass recorded was thought to be 28 years old.

Migration and spawning

During the late autumn and winter, bass migrate south, down the west coast of the UK, and west, along the south coast of the UK, aggregating into large shoals as they prepare to make their way to their overwintering/pre-spawning grounds at the western end of the English Channel. The trigger for this migration seems to be falling water temperatures, since a temperature of more than 9˚C is needed for successful spawning.

Not all bass migrate offshore in winter, but those which don’t are likely to be smaller fish, which have not yet reached sexual maturity. Numbers of fish which are running with eggs or milt might indicate late migration, or nearby inshore spawning areas. Occasional large fish are caught inshore during February, but whether these are loners, or indicative of a wider phenomenon is, as yet, unclear.

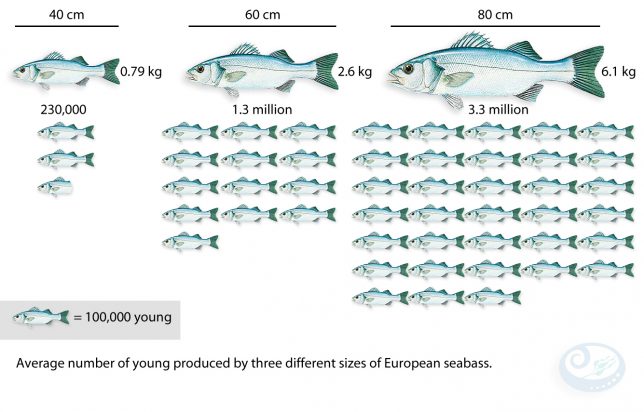

During the late winter and spring, bass begin spawning in the English Channel, and off North Cornwall; it may take place at other sites as well (such as off the Isle of Man). Day length and water temperature are thought to be important influencers on the onset of spawning. A mature female bass will produce between a quarter and a half a million eggs per kg of body weight per spawning season. Large older female fish, so-called BOFFFFs (Big Old Fat Fecund Female Fish) produce more and bigger eggs, which survive better. Once mature, bass can continue to reproduce for up to 20 years.

Year class success

The larvae arising from fertilised eggs at first drift towards the coast, assisted by currents and onshore winds (particularly if these are from a westerly direction). After about 2-3 months, the larvae begin to move actively into juvenile nursery habitats, possibly attracted by reduced salinity or higher water temperatures, arriving in June.

From about the beginning of July, the tiny (~3cm) ‘0’ group fry can be found in

estuaries. These are assessed in netting surveys during August and September (such as those carried out by Derek Goodwin’s group in Cornwall), the number found giving an indication of how successful the spawning has been for that year.

The following May and June, these surveys assess how well the ‘0’ groups have survived their first winter and become ‘1’ groups, the juvenile bass being susceptible to prolonged very cold spells.

The success of each year’s spawning, and its first-winter survival, determines the strength of the so-called ‘Year Class’ for that year. It can be seen from the above, that this is very dependent on environmental conditions.

‘0’ group, or ‘young of the year’ bass can also be found in rock pools on the open coast (for example in Dorset). It is not known how widespread this phenomenon is, or how much of a contribution it makes to stocks, but it could act as a buffer if there is a problem in the usual nursery areas.

Author: BASS Science Group, February 2021. With special thanks to Abi Carroll MSc

Feature Photo: Steve Richardson

© Bass Anglers’ Sportfishing Society 2021

*Information

Population Dynamics of the European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in Welsh Waters. Abi Carroll. MSc Marine Environmental Protection Thesis Bangor University 2013 – 2014.

Sea Bass. Biology, exploitation and conservation. 1994. GD Pickett and MG Pawson.

Life with Bass. 1998. DF Kelley.

Migrations, fishery interactions, and management units of sea bass (Dicentrarchus Labrax) in Northwest Europe. MG Pawson et al. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2007.

The influence of oceanographic conditions and larval behaviour on settlement success – the European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax (L.). ICES Journal of Marine Science (2017). C Beraud et al.

BOFFFFs: on the importance of conserving old-growth age structure in fishery populations ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2014.Hixon et al.

MAFF Fisheries Research Technical Report Number 99: Biogeographical identification of English Channel fish and shellfish stocks. MG Pawson.

Animal Diversity Web page https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Dicentrarchus_labrax/

Personal observations from juvenile bass surveys in Cornwall (D Goodwin/R Bradley) and from angling in Cornwall (R Bradley) and Dorset (M Ladle).

Average number of young produced by three different sizes of European seabass http://www.piscoweb.org/gallery/european-seabass-reproduction